Show me the money! Why marketers should focus on payback periods and cash flow in 2023

“Show me the money!” shouted Tom Cruise in that famous scene from Jerry Maguire. But now, it’s probably your CMO or CFO doing the shouting.

The economic downturn has hit hard. Money became expensive and investments plummeted. In less than a year, the mindset has shifted from “growth at all cost” to profit.

To adapt, marketers should adopt a new paradigm when running campaigns, one that focuses on payback periods and especially short[er] payback periods instead of the traditional LTV & CAC or long-term ROAS.

In this blog, we’ll explore how the economic climate has created a new stage in the evolutionary process, and what you can do about it to come out on top.

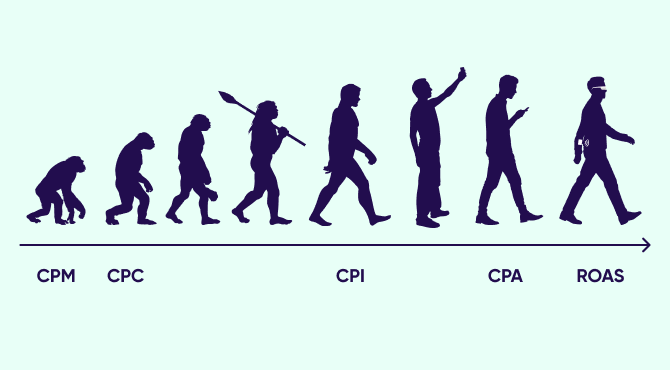

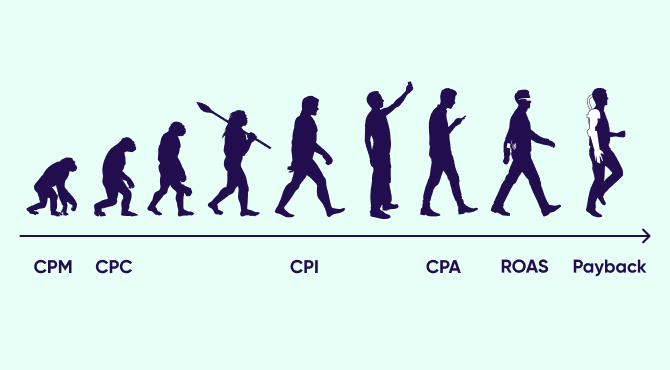

UA target evolution: moving down the funnel

The evolution of optimization in performance app marketing has been a rapid one. From impressions and clicks, to installs and CPI, to post-install metrics, LTV, and return on ad spend (ROAS). And all within 5-10 years. Darwin would have been impressed.

As we learned new lessons and started to use advanced analytical tools, we grew more sophisticated and advanced deeper into our funnels: from early events (such as registration or tutorial completion), and then towards more meaningful events (such as starting a trial, linking a bank account, watching 10+ ads or completing a first purchase).

In the last few years, most advertisers have shifted their focus to what actually moves their bottom line. This was the era of ROAS!

ROAS = Revenue / costs

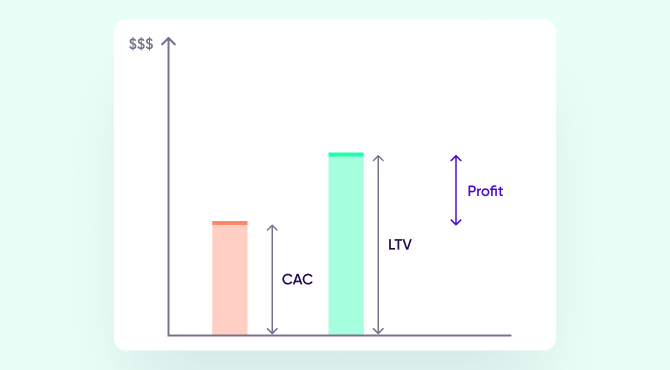

This simple formula is fully interchangeable with the cost per install (CPI) and average revenue per user (ARPU), or with the cost to acquire a paying customer (CAC), and the revenue per customer (LTV), usually projected (pLTV). So essentially, an interchangeable naming for ROAS is LTV:CAC.

What’s wrong with LTV & CAC?

In organizations where marketing & product work in silo (sounds familiar?…), marketers may have very little room to move monetization, increase conversions, and raise ARPU, and instead are tasked with reducing CPI and CAC.

This can lead to counter-productive results. By focusing solely on user acquisition cost reductions, there is also a high likelihood to change traffic quality, bringing users who convert differently than the previous cohorts, potentially harming the overall equation of ROAS.

For instance, using more ‘clickbaity’ creatives can reduce CPI but deceiving users at the top of the funnel can quickly lead to a drop in retention, which in turn leads to lower revenue. Advertising for “free signups”, running constant discounts & promotions can apparently bring more customers at lower costs in the short term, but if those customers retain less and spend less, this may not be a net positive in the long term.

Smart marketers look beyond CPI & CAC to consider the full impact of their decisions on ROAS. Smart organizations aim to break the silos between acquisition & monetization, which are almost always intertwined.

LTV is predicted, hence uncertain

By definition, “lifetime value” is revenue from the future. To estimate it and have it now, it needs to be modeled, or predicted. Such predictions are not as simple as they may look. They require large samples, analyst resources or tooling, and a relatively stable product.

In practice, no matter how sophisticated, LTV predictions have some inaccuracies and are hypothetical by nature. In the fast-changing world of mobile, predicting future revenue from past cohorts is a challenge because too many pieces of the puzzle constantly change: the marketing mix, the product experience itself, monetization schemes (new plans, promotions etc) and more.

Externalities add another layer of uncertainty: during a recession, consumer habits can change, and models will apply outdated behavioral data, with new cohorts generating less revenue than predicted.

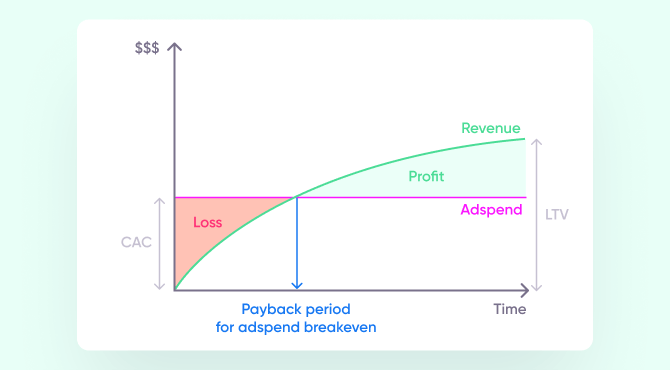

ROAS has no consideration for cash flow

Achieving a positive ROAS sounds great. But what if it takes 5 years to get there, and the first 2 years are negative? Well, in that case you’ll need to finance it.

With expensive capital, and a drought in funding, the ability to finance the period required to accumulate revenue and recoup the initial investment is hindered. This means that a company can die before it realizes its future profits.

Without looking at cash flow, a company could potentially go bankrupt despite having apparently profitable unit economics.

What changed? “The economy, stupid!”

The reason behind the latest UA metric evolution is external to mobile marketing. The global economic downturn is to blame.

In the current downturn, which started to pick up speed in the second half of 2022, inflation surged. As a result, central banks increased interest rates. In other words: money (capital) became and still is expensive.

Investors are no longer looking for “growth at all costs”, and instead ask for a path to profitability (or at least cash flow positive operations). VC-backed startups are pressured to make a U-turn from maximum growth to profitable operations, and capital for those operating with losses is scarce.

Aggressive growth goals with little scrutiny for profit & loss statements have led many to invest in the short term, with only very long term potential return.

2023 is entirely different, with all eyes on the balance sheet. This led to severe cost reductions, including waves of layoffs, but also a fundamental shift in marketing goals: bring profitable users!

In less than a year, the focus shifted from scale to cash flow balance. Welcome to the era of the payback.

The latest evolution of UA metrics: Payback

The fundamental difference between LTV:CAC and payback period:

LTV:CAC surfaces margin efficiency, looking at HOW MUCH money will come back

Payback surfaces cash efficiency, looking at WHEN the money will come back

Ad spend leads to cash going out immediately (or almost, credit lines can grant 30-90 days to settle), while LTV is realized progressively over time.

The payback period considers the difference between revenue & costs over time to determine the moment when revenue matches costs, from which point positive margins can be realized.

How it started:

How it’s going:

Payback beats LTV because it considers the cost of cash

With limited cash in the bank, and high uncertainty about fundraising opportunities, payback time forces marketers to consider the cost of cash and when revenue will come back.

By achieving shorter payback periods, companies can reinvest into growth earlier and faster than potential competitors who may depend on external investment.

For a number of companies in 2023, it’s not even a question of outpacing competition anymore, but mere survival.

Another benefit of the payback period is that it doesn’t require predicting future revenue and the high uncertainty that comes with it. It’s all about focusing on how much is recouped in the present, rather than making bets about the future.

The bottom line is that if a marketer is facing economic pressures now, the LTV of a year from now is just not, or at least should not, be on the agenda.

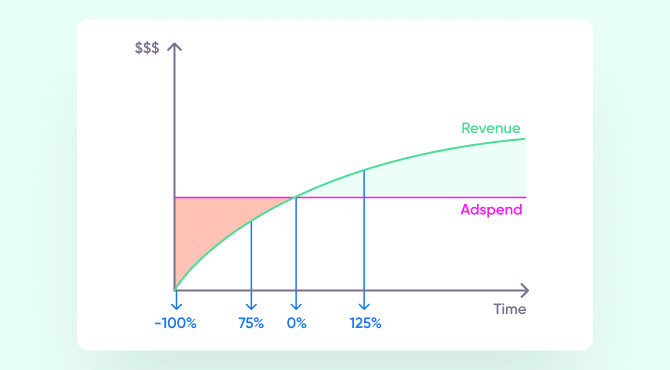

And unless early stage commands simplicity and speed over precision, marketers should be able to access the entire revenue development curve (actual and predicted) to get their own P&L for any cohort, at any given time.

This way, they can analyze, for specific segments (date, country, platform, sometimes even networks) when break even was achieved, what the “early proxy metric” used in UA optimization was at the time, how much realized profit was actually made up to date, and even potential future profit.

But what’s a good payback period?

“Less is more”

The ideal payback period is the shortest. In an ideal world, breaking even on ad spend takes place with the first purchase, within the first week or month after an install. In such a case, there is no need to deploy cash to finance further growth. It also means the company can sustain its budgets, theoretically financing from profits made by previous cohorts.

When first purchase/week/month payback is achieved, marketers can focus on their standard goals of scale (growth) and returns (profits) with less pressure from exact cash flow dynamics.

However, most companies are unable to achieve such an ambitious target, while many apps & games see payback times range between a month and a year.

Anything beyond a year is expensive (costs of financing capital deployment in advance) and highly risky due to the uncertainty of cohort development value and fundraising options.

Where each company will place the cursor is highly dependent: how much cash is left in the bank, what is the current payback period, how confident is the company in its ability to survive until another round of founding (or ideally, without!)

Closing the loop between ROAS & payback, what marketers should aim for

Day X: ROAS, meet payback.

In this article, I’ve described ROAS based on lifetime revenue, and “payback” as the period to break even.

But in practice, if defined properly, ROAS & payback are not that different after all. By setting a specific timeframe for ROAS instead of the “forever” LTV, and by considering the entire profit-investment dynamics and not just the break even moment, the two sides of the coin are very much the same!

This is why ROAS should always be specific, for example ROAS-day 7 or ROAS-month 6. Note that this also applies to other metrics (ARPU-day30, LTV-month12…). If you only use a single time frame internally, you may simplify the acronym, but it’s still good practice to keep in mind that this is not a “forever” metric.

Conclusion

Optimizing only for CAC is definitely not enough. It’s not even simply knowing when break-even is achieved (payback period). It’s all about how much money is made at any given point in time.

This level of detail requires quite sophisticated data processing, human resources, and brain power — you might get away with it in early stages by achieving instant payback instead, but in the long term, it’s the only way to avoid costly decisions, or miss out on big opportunities.

Remember! Improving your payback time is an effort shared across acquisition & monetization. It’s the only way to please your CFO when he shouts “show me the money!”

Since shorter = better when it comes to payback periods, especially during an economic downturn, the question is how to do it? Read the next post right here: Bring joy to your CFO: practical ways to shorten campaign payback periods