Mobile ad fraud is responsible for wasting billions of dollars in marketing budgets worldwide.

When discussing fraud’s true impact we must consider all aspects – direct and indirect – to properly assess the dangers of the online industry’s biggest threat.

Fraud tactics like malicious bots or device farms directly impact marketing campaigns by draining advertising resources on fake users who pose zero value. However, indirect impact poses a potentially bigger threat as long term ramifications hit advertisers’ decision making processes, budget allocations and audience targeting plans for future campaigns.

Responsible marketers must take the time to get familiar with fraud terminology and mindset to properly approach the issue.

Understanding how fraud operations view their business, who they are, and what is their motivation will help get a better understanding of how to approach the solution.

Getting familiar with common fraud tactics, technological tools, and industry vulnerabilities that allow fraud to thrive can help turn the spotlight on internal and external initiatives. These could help slow down and perhaps block the ever-growing fraud threat.

This comprehensive guide will cover the intricacies of online advertising fraud – specifically in mobile channels, follow its evolution alongside the industry’s development, featuring:

- Basic fraud terminology

- Indications and implications of mobile ad fraud

- Mobile ad fraud evolution

- Fraudster profile

- Common fraud methods

- Current market and main vertical analysis

Mobile ad fraud isn’t going away anytime soon.

To manage and treat this issue properly we must first dig deep and thoroughly understand it. Only then can we roll up our sleeves and start cutting out malicious and fraudulent entities from our activity, saving precious budgets in the process.

The more educated we are the better equipped we become to take on the fraud challenge.

What is mobile ad fraud

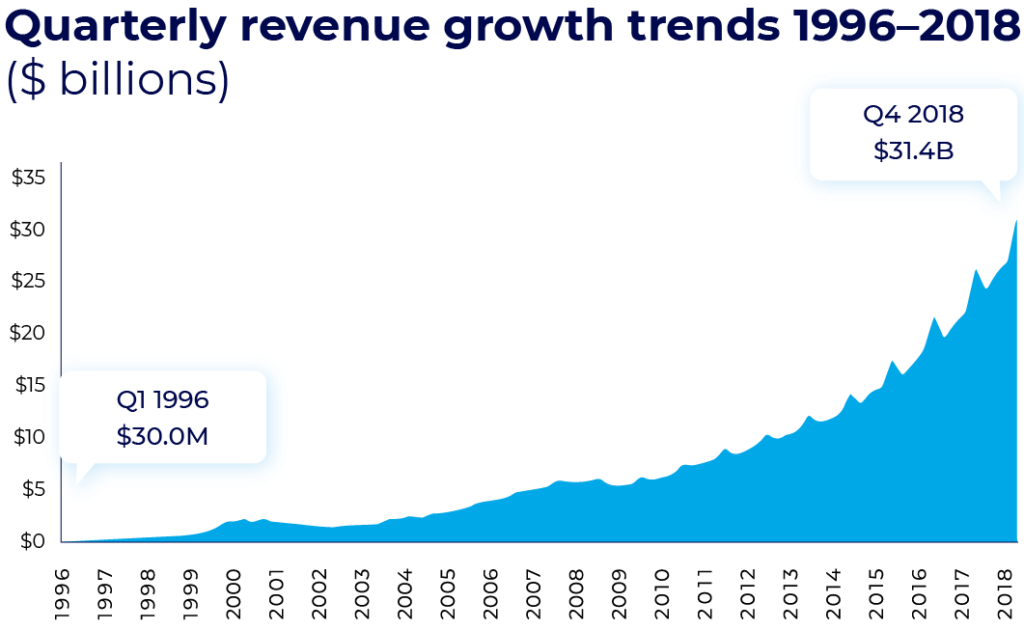

Online advertising is thriving.

It’s an industry where billions of dollars are spent annually across a variety of channels at an increasingly large scale.

Since the earliest days of the internet and its introduction to households worldwide, online ads played a big part in its monetization options. In many ways, digital advertising made websites and apps a profitable business.

As the spread and reach of online channels grew, advertisers started allocating more significant budgets into online advertising. This was done in an attempt to reach a more accurate audience based on interests and user behavior.

Alongside the growth in advertising budgets, online ad fraud has been steadily growing and developing, applying deceptive practices to try and obtain a piece of these funds.

The estimated magnitude and cost of online advertising fraud varies dramatically between different sources.

Conservative estimations point at billions of dollars lost annually to fraud with current estimations varying between $6.5 billion and $19 billion annually (eMarketer).

The range above highlights the difficulty of accurately estimating the true impact of online ad fraud.

Ad fraud techniques constantly evolve, develop, and challenge the industry’s infrastructure by manipulating new technology to its benefit.

What is mobile ad fraud?

Fraud is a general term used to describe deception.

That means it can be applied to any industry or type of transaction.

Fraudsters aren’t picky when it comes to industry or vertical – illegitimate actors will try to manipulate or exploit any ecosystem’s rules to gain an unfair advantage or obtain funds in a way that violates basic rules and standards.

Wherever the money is – fraud will likely be there.

To understand what mobile ad fraud means, let’s first understand other types of fraud to avoid confusion:

Fraud

A type of scheme that can or cannot rely on online tools to be conducted. One party tricks one or more victims into believing they can provide value in exchange for goods, using false advertising or false presentation of information.

Examples:

- Ponzi schemes

- Pyramid schemes

- Fyre festival

Online fraud

A type of scheme which relies on online tools (email, social media, SMS, etc.) to reach its victims and elicit an interaction (click on malicious links, information exchange, download malicious software etc.) and use it to manipulate and exploit users.

Examples:

Online ad fraud

A type of scheme where fraudsters manipulate online advertising conversion flows to falsely obtain advertising budgets. CPM, CPA, CPS, and other advertising models are manipulated by generating fake impressions, clicks, sales, and even users.

Examples:

Mobile ad fraud

A subgroup of online ad fraud, conducted via various mobile devices such as smartphones and tablets, and considered under two main channels: Mobile web (web browser located on mobile devices) and Mobile app (mobile application environments).

Examples:

- Install hijacking

- SDK hacking

- Mobile device farms

Fraudulent vs. invalid traffic

A distinction must also be made between fraudulent traffic and invalid traffic.

Online advertising fraud intentionally manipulates conversion flows and aspects in the conversion path to steal advertising budgets. Invalid traffic, however, is simply traffic that falls outside the campaign rules and advertiser expectations – whether intentionally or unintentionally.

Common examples:

- Wrong geo targeting

- Unwanted traffic sources (adult, incentivized, etc.)

- Exceeding campaign caps

- Wrong ad specs or formats

Mobile advertising terminology

Organic user – A user who installs and launches an app without any ad engagement during the install process.

Non-organic user – A user who installs and launches an app after engaging (view or click) with an ad.

Attribution provider – A measurement platform connecting between advertisers and publishers. The attribution provider will measure the advertiser’s campaign activity through dedicated URLs and notify both the advertiser and the publisher once a non-organic install occurs through postback server messages.

Ad – An advertisement presented on the publisher’s media for the advertiser’s app.

Ad Impression – A measured ad view engagement.

Ad click – A measured ad click engagement.

Install – An app installation from the app store to the user’s device (this can be organic or non-organic (NOI))

Launch – The first launch of the app on the user’s device – an official app install will only be attributed once the app is launched for the first time.

In-app event – A measured benchmark within the app – specific level reached, in-app purchases etc.

In-app purchase – Virtual or physical goods bought through an app’s in-app store.

Mobile attribution, explained

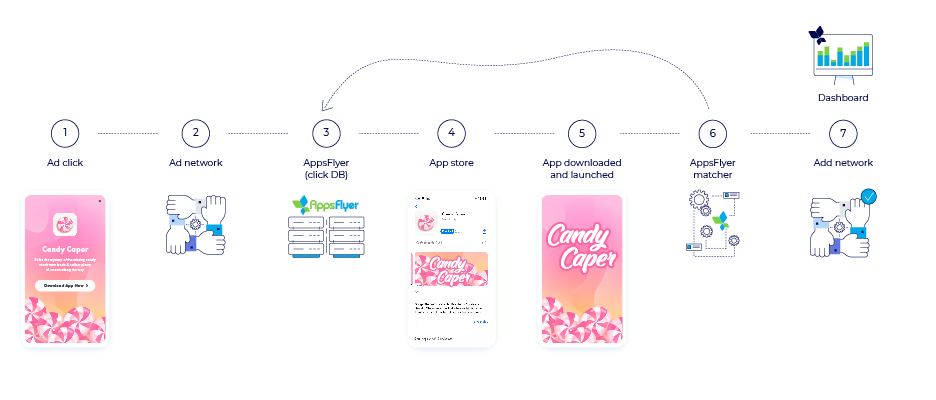

To understand how mobile ad fraud works, let’s first review the standard flow for app install attribution.

- A user clicks on an ad that appears on their mobile device.

- The click will be registered with the media partner who is responsible for the ad’s placement, while the user is redirected to the appropriate app store based on their device OS.

- The click will then be recorded with the attribution provider.

- The user reaches the app store and downloads the app.

- The user launches the app for the first time.

- The attribution provider’s algorithm matches the app’s install data with its click engagement data and records it in an attempt to see if the user is organic or not.

- Once an ad engagement is matched to the app install the user is labeled as non-organic.

The credit for their install will be attributed to the appropriate media partner and will be displayed on the advertiser’s dashboard.

The above is a simplified explanation of how basic “last click attribution” models work.

This mobile attribution method was first introduced by AppsFlyer in 2011 and has since become the standard measurement and attribution model used across the industry.

Fraudsters will attempt to identify and exploit loopholes, failures, and other opportunities within this process.

Mobile ad fraud basics

Mobile ad fraud basics

Mobile ad fraud implications trickle down to each and every aspect of an advertiser’s marketing initiatives, affecting current activities and future activity alike.

Lost budgets (direct and indirect)

The most obvious implication is the direct financial loss fraud creates. According to AppsFlyer’s latest mobile ad fraud data study, 15% of global mobile media spend is wasted on fraud.

These lost budgets could have produced value for advertisers had they been wisely invested in other profitable channels. This is considered as the alternative cost and could potentially pose a greater risk for advertisers due its long term effects and scale.

Polluted data

Fraud can lead advertisers into investing and reinvesting in “bad” media channels due to the pollution of data being analyzed.

Once fraud infiltrates the data mix, it becomes almost impossible to tell apart real users from fake ones and organic users from acquired ones.

Bottom line? Advertiser’s data becomes polluted and unreliable.

Drained resources

Above anything else, fraud is an enormous waste of time and human resources. Entire teams spend countless hours working on reconciliation and clarifying where anomalies are found within their data.

Ecosystem impact

While advertising budgets are stolen, advertisers are far from being the only ones impacted.

Fraud damages are felt across all entities and players within the marketing ecosystem.

Marketing tech vendors

Mar-tec vendors rely on healthy advertising budgets to prosper, develop, and offer additional services.

As fraud engrosses more marketing budgets, advertising ventures become less profitable for many advertisers. Mar-tec companies who rely heavily on these budgets are hit by a lower scale of marketing initiatives.

This serves as a double negative, as mar-tec solutions often help advertisers better measure their activity, optimize campaigns, and even help protect them from fraud.

Media partners (ad networks)

Fraudsters exploit the ecosystem’s complexity and the many mediating entities within it to remain undetected, with many ad networks unaware of fraud polluting their traffic.

A lack of fraud treatment could mean losing an ad network’s reputation and risking its future business with leading advertisers, as advertising budgets shift towards SRNs – limiting their media portfolio in exchange for cleaner traffic.

Moreover, legitimate networks often lose credit for quality users they provided due to attribution hijacking tactics, stealing their credit using fake clicks.

Publishers

High profile app and website owners rely heavily on revenue generated by traffic monetization.

Domain spoofing fraud aims to directly steal revenue from these sources by pretending to sell their traffic – inserting their domain name artificially to attribution URLs. These actions hide fake or low quality traffic bought cheap and resold through ad exchange platforms for higher rates.

Mobile ad fraud indicators

Much like other crimes, mobile ad fraud also has its clues and indicators to help identify it and flush out its operators.

The data collected by attribution providers can be analyzed to identify anomalies in user behavior, device sensors, and more. These can help paint a picture of what legitimate activity patterns look like and in turn highlight abnormal behavior.

As data analysis plays a big part in identification – reliance on a larger database makes fraud identification efforts more accurate, identifying more fraudulent patterns faster and more efficiently.

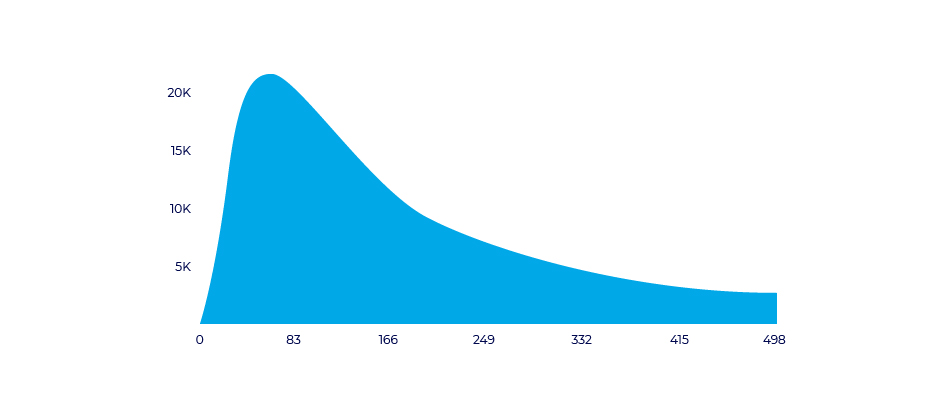

CTIT

Click to install time measures gamma distribution between timestamps in the user journey – the user’s initial ad interaction, and their first app launch.

CTIT can be used to identify different cases of click based fraud:

- Short CTIT (under 10 seconds): possible install hijacking fraud

- Long CTIT (24 hours and after): possible click flooding fraud

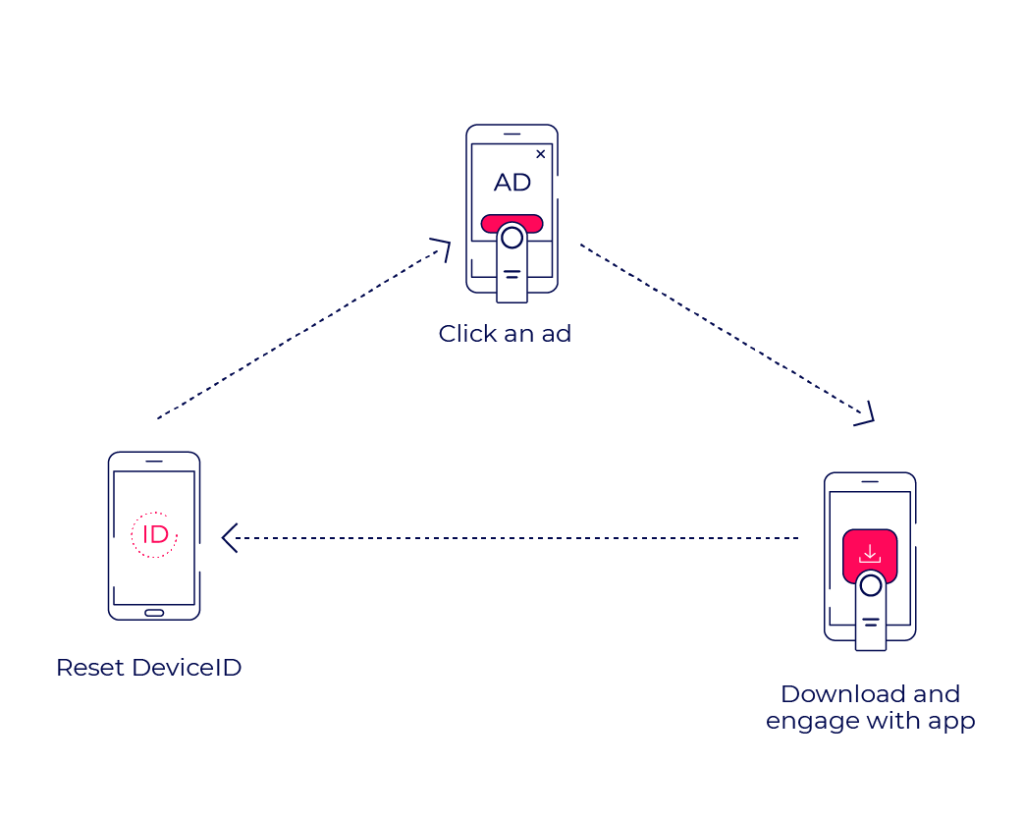

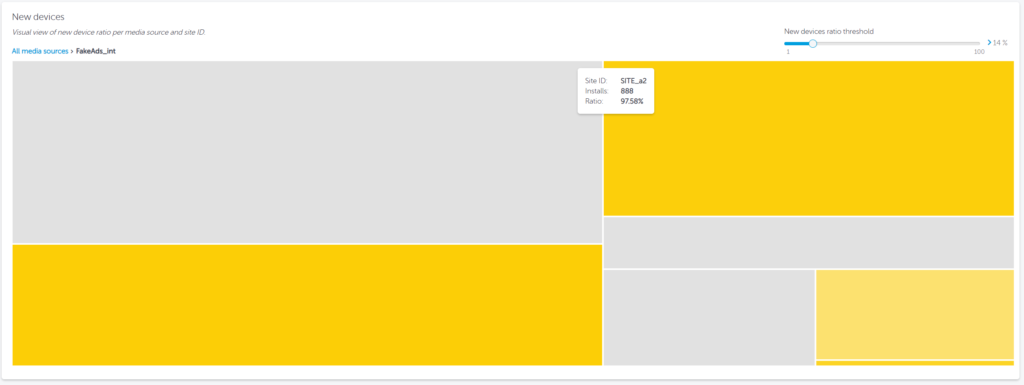

New device rate

New device rate will highlight the percentage of new devices downloading the advertiser’s app.

New devices are of course normal, as new users install apps or existing users change devices. However, one must keep an eye on the acceptable NDR for its activity, as this rate is determined by new Device IDs measured. As a result it can be manipulated by Device ID reset fraud tactics, very common with device farms.

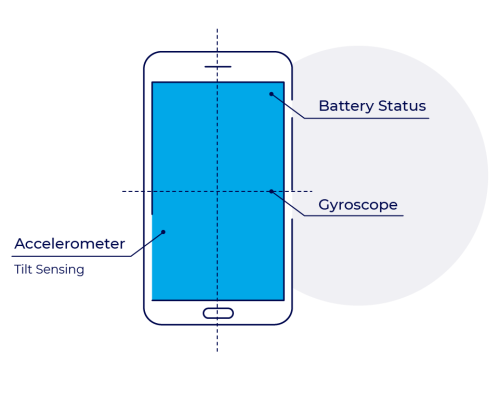

Device sensors

Biometric behavior analysis relies on hundreds of device sensor indicators from the device battery level to its angle and more.

These indicators help create a profile for each install – analyzing the device and user behavior per each install and their compatibility to normal trends measured with real users.

Limit ad tracking

Limit Ad Tracking is a privacy feature that allows users to limit what data advertisers receive about the activity generated by their devices. When a user enables LAT, advertisers and their measurement solutions receive a blank device ID in place of a device-specific ID.

Fraudsters attempt to hide their schemes by enabling LAT on their devices. This KPI is relevant only for Google and iOS advertising identifiers. Amazon, Xiaomi, and more use other identifiers.

Conversion rates

A conversion rate describes the translation of one action to another, this could mean ad impressions into clicks, clicks into installs, or installs to active users. An advertiser’s knowledge of its expected conversion rates at any point in the user journey can help prevent fraud infiltration.

A rule of thumb in terms of conversion rates is to suspect that anything that is too good to be true, likely isn’t true.

Artificial intelligence

Artificial intelligence has become a common fraud indicator, as it allows to apply fraud identification logic at scale. AI helps indicate instances untraceable by humans at any scale.

Machine learning algorithm (i.e. Bayesian networks) combined with a large mobile attribution database will ensure an efficient and accurate fraud detection solution.

A fraudster’s profile

When examining the current profile of common fraud operators we notice a misconception of market perceptions.

Many marketers perceive fraud as a malicious operation carried out from secret locations. The fraudster is often thought of as a hacker wearing a hoodie or a mask.

In reality, fraudsters are anything but secretive, with some of them even displaying their activity out in the open. However they often don’t consider their activity to be fraudulent, but rather regard it as a service.

The average fraud operation can appear like a mainstream tech company, and even seem legitimate. The use of various bots, emulators, and other malicious tools are referred to as “products” or “software releases” rather than fraud.

These companies operate from trendy offices, offer pension programs, and benefits. They employ bright minds, experienced engineers, and operate sophisticated BI teams as they choose their targets wisely and develop their “products” to bypass their target’s defenses.

They are calculated, goal oriented, and operate ROI driven, large scale operations.

In order to effectively take on the ad fraud challenge we must first acknowledge that the people operating it are just as sophisticated and forward thinking (if not more) than the ones looking to block their attempts.

Another common misconception is that fraud is usually driven by ad networks and malicious media sources. While this can sometimes be the case, fraud can still be driven from various directions, using the industry’s structure to encourage its growth.

Advertiser fraud

The online industry’s roles are dynamic, anyone involved can act as advertiser, publisher or mediator at any given point. Malicious apps carrying malware or adware need to reach large audiences in order to operate their schemes at scale – they to rely on marketing campaigns.

These apps can appear harmless at first, but initiate or support malicious activities once downloaded to user devices.

It’s important to examine each app carefully, noting the backend credentials and permissions and how they are used.

Mediator fraud

A mediator can be any entity placed between the advertiser and its publisher.

There are numerous ways in which mediators can manipulate transactions for their benefit.

One of these manipulations is domain spoofing, where a publisher’s domain or app is altered by the mediator to appear more attractive and require higher CPIs. Another, is ad stacking, where a single ad placement can host several ads simultaneously, showing visibility to only one ad.

Publisher fraud

Publishers themselves can often initiate fraud using numerous tactics that help boost the value of specific media assets.

A publisher can operate bots to constantly remain active on their app and generate impressions for ads presented to them. These bots can even initiate clicks and in-app engagements with the apps.

Display fraud tactics are also very popular with some publishers, as they attempt to squeeze more out of their own media offering, using invalid ad placements and misrepresentation of media quality.

User fraud

In a market where the absolute majority of apps are offered for free, in-app economies rely heavily on the app’s ability to convert free users to service acquiring users at very specific rates.

User fraud occurs when users try to trick an app’s economic structure in order to gain better positioning or use its services for free.

From resource draining bots in gaming apps to unlocking swiping limitations in dating apps, these actions bypass the app developer’s intended user experience. In doing so, users harm the app’s means of generating revenue.

Common fraudster tools

Fraudsters are inventive and creative, constantly improving tools in their disposal to further develop their activities.

Common legitimate tools used by developers, advertisers and users will often be manipulated and used to exploit specific functions that create opportunities for fraudsters.

Device emulators

Emulators are a common tool for legitimate game developers as they create a virtual device environment to test different app features. Fraudsters, however, use these emulators to mimic mobile devices at scale and create fake interactions with ads and apps.

Emulators are easy to download, enable seamless recreation of fresh devices and users, and can be operated at large scales using bots and scripts.

VPN proxy tools

A VPN works by routing the device internet connection through a chosen VPN’s private server rather than the internet service provider (ISP). When data is transmitted to the internet, it comes from the VPN rather than the device.

Fraudsters abuse this tool to mask their operations and hide their IP addresses to avoid being blacklisted. This tricks advertisers into thinking that their engagement originated from desired locations.

Malware

Malware is a malicious software intentionally designed to cause damage to a device, server, client, or computer network. Fraudsters design and develop different types of malware.

These developments help manipulate security breaches and loopholes by infiltrating devices and servers, falsify data, and exploit advertisers and users alike.

The evolution of fraud

Fraud has always been a part of the online advertising industry. As long as there was money to be made, even for basic CPC campaigns, fraud was an integral part of the advertising equation.

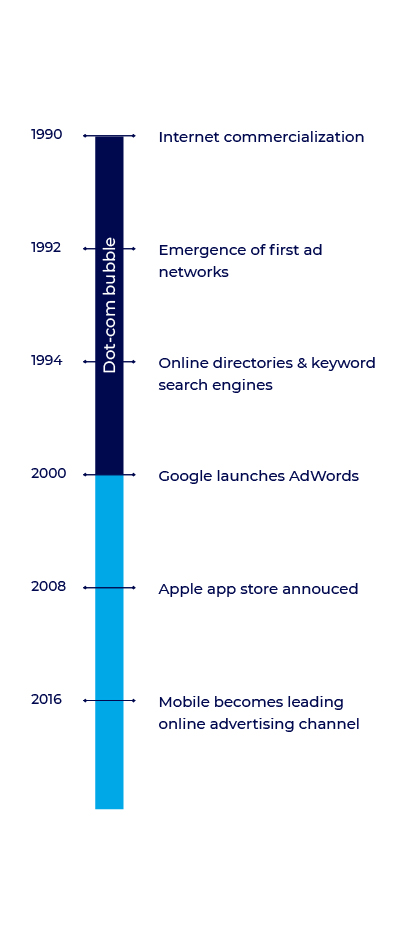

Mediated ad networks started appearing around the early 1990’s to help connect between advertisers and websites.

The 90’s dot-com boom increased publisher variety and scale significantly, which opened a door to various ad networks. Additionally, the first directories such as Yahoo! directory and keyword search engines like Alta Vista emerged in order to help users reach destination sites and navigate between a plethora of websites easily.

Early ad fraud methods in the late 90’s and early 2000’s were mostly focused around variations of desktop based click spamming and search engine manipulations.

In 2008 the Apple App Store was announced, introducing a new era where internet access is available through mobile devices.

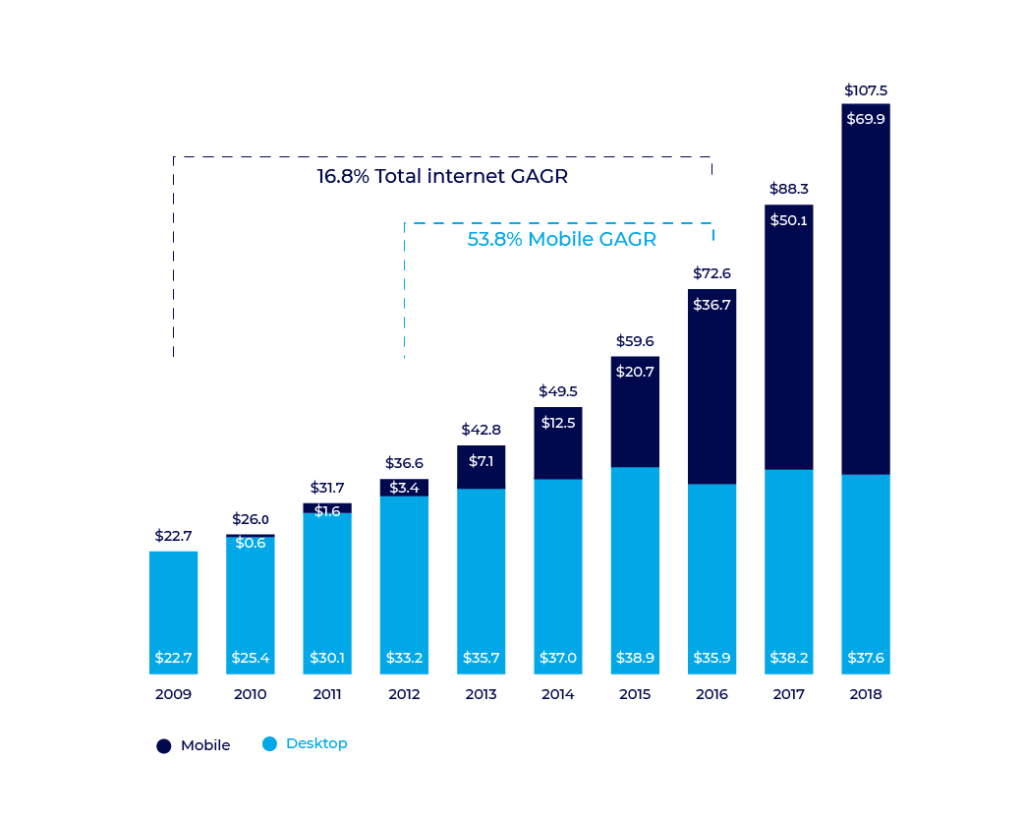

The introduction of app environments and mobile web played a significant role in the surge of online advertising during the 2010’s gradually taking up a bigger piece of the advertising pie.

Up until 2010, desktop activity was still the main focus point for advertisers and fraudsters alike. As mobile budgets grew, fraudsters gradually started shifting their focus towards mobile – initially applying common desktop fraud methodologies into mobile activity to test the new environment’s potential.

App install fraud became more popular over time as fraudsters exploited the industry’s interest in expanding towards the mobile front.

App store rankings became the new focus point for advertisers – who opted for “burst” campaigns to gain large install quantities at very short time frames. This offered an open door for fraudsters to exploit incentivized and low quality channels, spamming advertisers with fake users.

As app store ranking algorithms evolved, “burst” tactics became almost obsolete. App developer’s understanding of the new mobile landscape matured as well, putting their focus on quality, active users rather than inflating install numbers.

As the industry evolved, greater mediation points in the form of ad exchanges, SSPs, DSPs, media agencies, and others were added to the journey between advertisers and publishers – each with their own view on transparency, traffic quality and delivery standards.

Industry complexities currently allow fraud to flourish.

Fraudsters exploit transparency loopholes, reporting standard inconsistencies and even technological development attempts to conduct their schemes at different scales across various platforms.

Online publisher or media source accounts are easy to create and disguise across a plethora of mediation platforms available using shell companies and other masking techniques.

These help hide the fraudster’s operation as it mixes with other sources in an ocean of data and is often only identified by a generic ID which separates the malicious activity from a company name.

Once hidden or masked CPM, CPA, CPS and other advertising models are easy to manipulate by generating fake impressions, clicks, sales, and even users. Even when caught or blocked, a fraud operation can easily repackage itself under a new ID or business entity and resume its fraudulent activities.

Mobile ad fraud methodology

Mobile ad fraud methods are varied and apply different malicious techniques based on several parameters:

- Fraudster target and goal

- Exploited weaknesses or loopholes

- Available technology

- Level of sophistication

- Financial capabilities

The above are all integral parts of the equation for deciding the type of fraud, scale and target that the fraudster is looking to target.

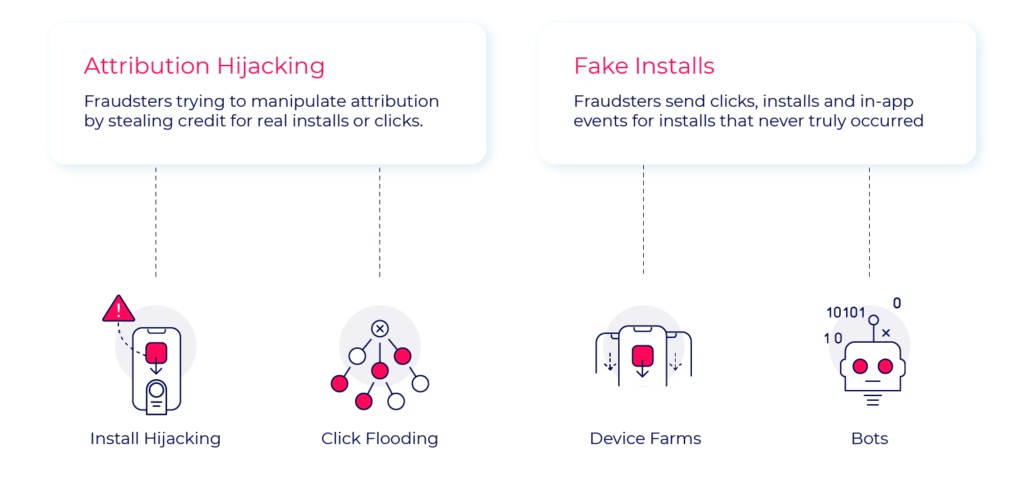

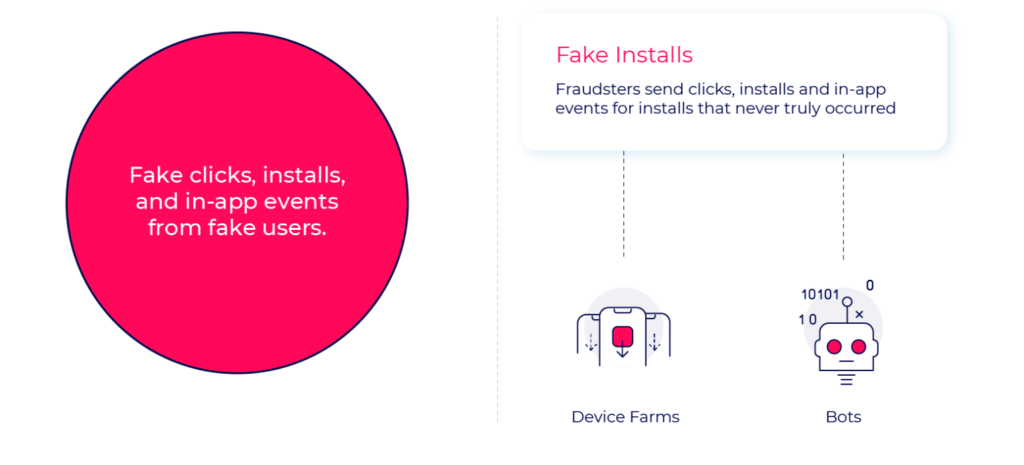

When examining the most common fraud methods, these can be broken down into 2 main categories: attribution hijacking and fake installs.

Fraud methods

The main difference between the two categories are the users.

| Real users | Fake users | |

| Real engagement | Clean traffic | N/A |

| Fake engagement | Attribution hijacking | Fake installs |

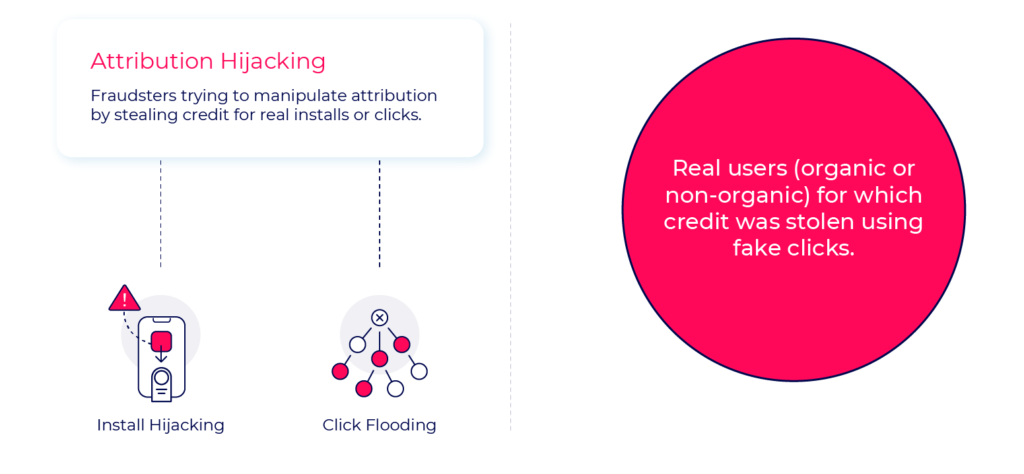

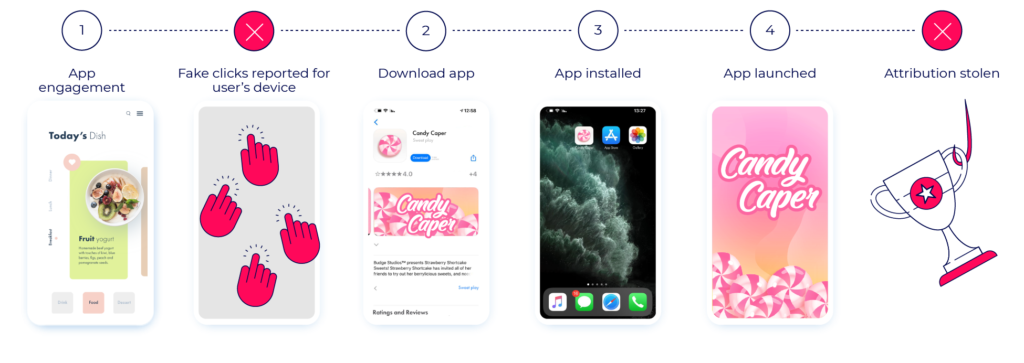

Attribution hijacking

Attribution hijacking methods rely on real users (organic or non-organic), using fake click reports to manipulate attribution conversion flows. Injecting clicks in different points across the user journey will help them steal credit for installs and users provided by other media sources.

With fake installs, the entire user journey is fake. Impressions, clicks, installs, in-app events and even users are all fake.

While both cases damage the advertiser’s activity and resources, with Attribution hijacking tactics the users are still real and provide some value. Unlike fake installs who present zero value to advertisers, often making their entire user acquisition data worthless.

Specific methods under these two categories are varied, the most common methods currently used are examined below.

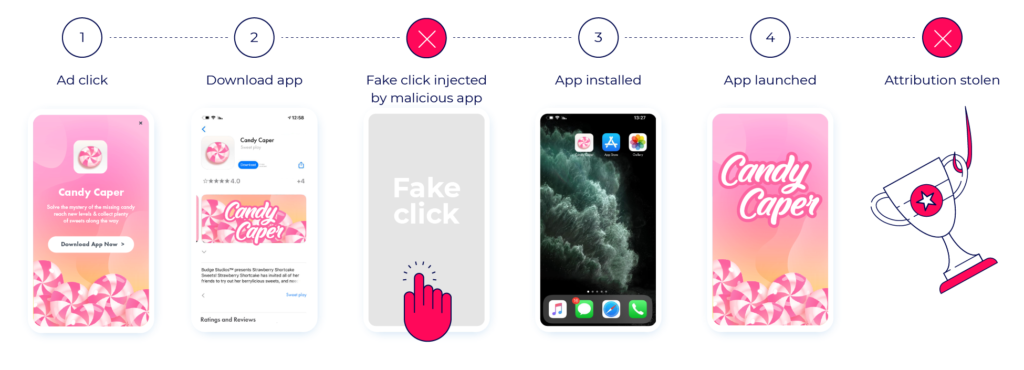

Install hijacking

Install hijacking is a type of fraud where fraudsters “hijack” credit for an install generated by another media source.

Common techniques include sending false click reports or injecting false referrer data.

A user would click on an ad presented by a legitimate media partner, and will be directed to the PlayStore to complete the download. Once the download process starts, the Android device will inform the other apps on the device that a new app is being downloaded – this is done using a standard android broadcast.

This broadcast – available for any app – will then trigger a malware that had already exited on the user’s device within another app.

The malware will generate a fake click report on behalf of the fraudster – making it appear as if the fraudster is the one who generated the install. This will manipulate the last click attribution model, placing the fraudster as the one who generated the last registered click.

Once the app is launched, attribution will be stolen.

Exploiting a basic attribution model is relatively simple for the fraudster. However, this type of fraud is also relatively simple to identify using standard CTIT measurements and anomaly detection.

The fraudster’s click will naturally come in significantly later than clicks driven by legitimate sources.

Thus a short CTIT rate will indicate a case of attempted install hijacking.

Sophisticated fraud solutions can use click timestamps to attribute the install to its rightful media source using attribution calibration – minimizing damages on the advertiser’s reporting and retargeting data.

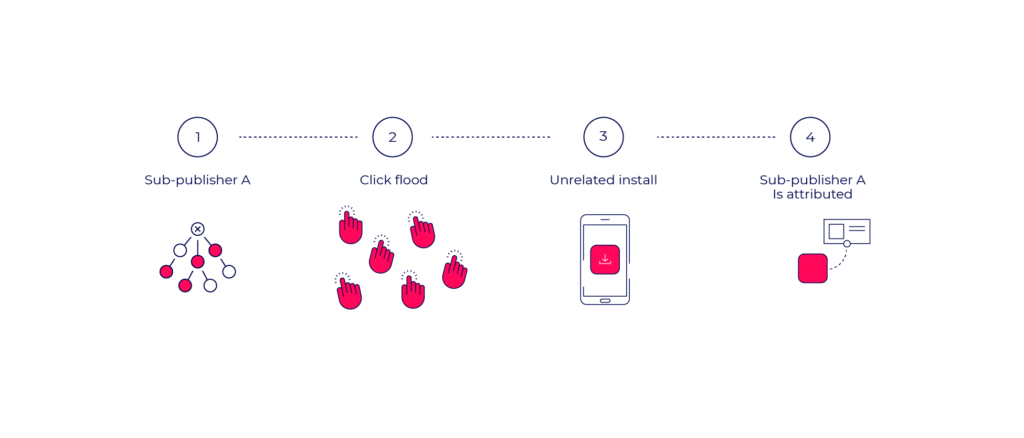

Click flooding

In click flooding, fraudsters send a “flood” of false click reports from, or on behalf of real devices. Once the actual device downloads the app, the sub-publisher is falsely credited with the install.

Click flooding often targets organic users as it aims to take credit for their activity using probabilistic methods.

The fraudster would create publisher accounts across various attribution channels and pull attribution URLs for as many apps as possible.

Populating large masses of clicks with real device details can be done either by malware from user devices or by purchasing user data in nefarious channels (dark-net).

Clicks can be generated randomly or in a calculated manner based on the user’s installed apps or browsing activity.

Once users organically reach the App Store or Play Store and download an app, a click is already falsely associated with them, even though no ad was viewed or clicked.

Once the app is launched by the user, the fraudster is credited with an organic install that the advertiser should never pay for.

Click flooding attempts can be identified and blocked using different methods like very low conversion rates and CTIT measurements.

A long CTIT rate will likely indicate attempted click flooding, as clicks are constantly sent on behalf of users regardless of their activity or time of app installation.

Attribution hijacking – key takeaways

Complexity

Attribution hijacking fraud methods are considered relatively simple to initiate and operate.

They require quite basic technology and their reliance on real user data means that the majority of data is generated organically rather than falsely inserted into the postback information by the fraud operator.

Potential gain

The potential gain from attribution hijacking fraud is considered limited for several reasons.

Its relative operation simplicity also makes it quite simple to detect by fraud detection solutions by measuring CTIT timestamps anomalies. The operations are also limited in potential scale as they rely on real users – limiting them to a finite number of potential devices to exploit.

Business implications

As attribution hijacking methods rely on real users, advertisers would still receive some value from these users. However the advertiser’s marketing budget allocation is manipulated, meaning that quality publishers who made these installs possible are not rewarded as the credit for their hard work is stolen by malicious sources.

This affects any future budget allocation decisions made by the advertisers, as fraudulent sources appear to provide quality and legitimate publishers are pushed aside.

Device farms

Device farms are locations full of actual mobile devices clicking on real ads, downloading real apps, while hiding behind false IP addresses and fresh device IDs.

Often associated with remote parts of the world, device farms could be located in any space that can hold and operate a large number of devices – from bedrooms to warehouses. Very popular in the early 2010’s, these operations can be operated either by low paid employees or emulators, working around the clock on constant app engagement and device resetting.

The more efficient the operation is at creating engagement and resetting its device identities, the more revenue it can generate.

The relative simplicity of this method, combined with lower mobile device prices and economic difficulties, introduced a second wave of device farms in common western households as a means of creating additional income.

How to identify device farms

New devices are not uncommon and are expected to be found in any campaign, as users constantly upgrade or change their devices for various reasons.

However, a campaign’s New Device Rate should be monitored for anomalies.

High NDRs, combined with other parameters, are a possible indication of device farm activity operating with device ID reset at scale.

According to AppsFlyer’s data, common new device rates shouldn’t surpass 10%-20% of the campaign’s activity.

Bots

Bots are malicious codes that run a set program or action. While bots can be based on real devices, most bots are server-based. Bots aim to send clicks, installs and in-app events for installs that never truly occurred.

Bots can be applied to automate any action within the user flow or the app itself, including the methods presented earlier. They can be used to mimic real user behavior based on behavioral biometrics data collected by malware on user devices.

These “trained” bots appear “real” making them harder to identify and block.

Fraudsters adapt to advanced detection logic and train bots to run through in-app engagement measurement points appear as engaged “real” users. This presents double value for fraudsters as they appear as quality publishers who deliver engaged users, as well as gain CPA revenue from in-app events.

Some fraudsters even offer their bots as services such as harvesting game resources, passing levels, and generating revenue for third parties in what’s considered as FAAS (Fraud as a Service).

Fake installs – key takeaways

Complexity

Fake installs fraud methods are considered more complicated to operate and maintain.

The fraudster would require a very high level of technological abilities and sophistication to not only design an elaborate mechanism to continuously generate users, but also randomize that behavior at scale to avoid sophisticated pattern detection algorithms.

Potential gain

While more complicated to operate and maintain, once successful a fake user fraud scheme presents unlimited potential scale.

Unlike attribution hijacking schemes which rely on real users, bots and device farms don’t require real users or even real devices to operate.

Faking the entire user journey makes their operation potentially limitless and profits much higher.

Business implications

Unlike attribution hijacking methods, with fake installs the advertisers receives zero value.

Users are completely fake, any interaction made within the app is pre-programmed to drain even more CPA rates from the advertiser and cause more damage. the advertiser’s data will often be worthless as these fake users mix with real ones, making retargeting efforts pointless.

SDK hacking

One form of bypassing install fraud detection is by fraudsters feeding false information into the advertiser servers. SDK hacking (AKA spoofing) is a type of bot-based fraud, often executed by malware hidden on another app within the user’s device.

In SDK hacking, fraudsters add a code to an app (the attacker) which later generates simulated ad clicks, installs and engagement signals to the advertiser’s attribution provider on behalf of another app (the victim).

When successful, these bots can trick an advertiser into paying for tens or hundreds of thousands of installs that did not actually occur, as their servers are tricked into believing that installs indeed took place.

SDK hacking is a common issue for attribution providers with weaker SDKs or poor security infrastructure.

Simple security loopholes like a poor encryption mechanism (easier to decipher) or relying on open source technology (presenting code publicly for fraudsters to review) could pose as a potential open door for fraudsters to manipulate the attribution provider’s code or reverse engineer it.

A closed source, encrypted SDK (like AppsFlyer’s) provides better protection from reverse engineering and code manipulation, by not revealing the code publicly and masking its encryption logic, making it significantly harder to breach.

It’s important to note that no method is foolproof, as sophisticated hackers can potentially hack anything they set their sites on. However, better security and protection on the code and infrastructure level will minimize risks and make hacking attempts a bad investment for fraudsters.

In-app (CPA) fraud

In 2008 the App Store introduced the CPI promotion model – the dominant promotion form for app developers – rewarding media partners for generated app installs.

The CPI model opened the door to install fraud, which started delivering poor user value for advertisers. In an attempt to reduce the damages of install fraud, a new promotion mechanism was introduced – CPA (cost per action).

CPA models relied on a base assumption that a user who’s active beyond the point of installation would be regarded as a quality user and not a fraudulent one.

Advertisers (mostly from the gaming vertical) started mapping out key in-app events within their apps to measure user LTV (lifetime value):

- Level reached

- Tutorial completed

- In-app purchase made

The CPA rates for these events were often significantly more rewarding than the CPI offered, as they reflected an engaged user with higher LTV and acquisition value. With time more advertisers from various verticals adopted the CPA model with the assumption that this could provide sufficient protection from ad fraud as well as drive better user value.

However, as stated earlier, fraudsters follow the money – very quickly catching up with the new CPA game. What was once considered a fraud-free promotion model, is now infected with ad fraud.

Advertisers who managed to decrease their install fraud rates by shifting towards CPA (gaming, shopping, and travel verticals mostly) are now hit harder through sophisticated bots specifically designed to bypass install fraud detection, and hit rewarded in-app events, crushing advertiser in-app economies.

In-app purchase fraud

In-app purchases and in-app marketplaces are a common method for advertisers to generate revenue by selling actual (merchandise, services, and products), or virtual goods (game resources, artifacts, etc).

A definite majority of apps rely on free or freemium business models (under 4% paid apps), where the app download is free and revenue generated from ads and in-app purchases as stated above. An app’s entire business model could often revolve around its ability to generate these transactions at certain rates, and they reward their publishers accordingly when these are generated.

CPS (Cost Per Sale) rates are considered the highest in the market, as they reflect the highest quality of users and guaranteed income for the advertiser.

These can vary from fixed rates to percentages from each sale. Fraudsters will do whatever possible to get hold of this activity, as they reflect a much bigger payday per successful action than CPI, thus requiring less successful actions to generate revenue.

As in-app fraud continues to evolve and improve, an increase of fraudulent in-app purchase attempts is also noticeable, hitting all major verticals.

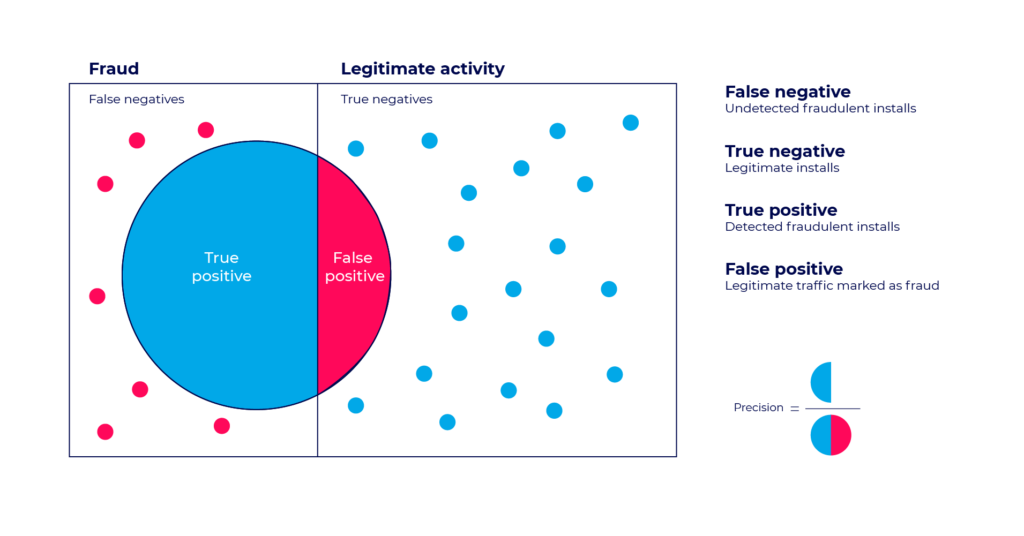

False positive test

A false positive is a case where a legitimate install is falsely flagged as fraud.

The false positive test sets the allowed precision level for fraud detection algorithms.

The higher precision level is – the more conservative the fraud detection is. The lower precision level is – the more permissive the algorithm will be. More fraud will be detected, but at the price of more false positive cases.

Higher precision = lower false positive rate.

As damaging as mobile ad fraud can be to an advertiser’s business, false positives could potentially be worse, as they indicate cases where an install was falsely identified as fraudulent.

Unlike true positive cases, where real fraud is identified and fraudulent sources get exposed and blocked, a false positive case potentially penalizes legitimate sources. This could harm the advertiser’s relationship with its quality media partners rather than protect it from malicious ones.

Any responsible fraud solution should keep its false positive rate as minimal as possible, in order to protect its integrity and credibility while protecting its client’s best interest.

That being said, fraudsters are fully aware of fraud prevention vendors’ intentions of avoiding false positives, so they deliberately mix legitimate installs into the fraud mix. This isn’t done as an attempt to improve their traffic in any way, but rather whitewashing it, only to be later used as a counterclaim when their activity is blocked.

Mobile ad fraud – market status

To understand just how big the impact of mobile ad fraud is, we need to take a broader look across main industry verticals, and the clear difference between non-gaming apps and gaming apps.

Gaming advertisers are known as savvy digital marketers, very data driven with high awareness to every point in their user journey, which leaves very little space for fraudsters to operate.

Gaming advertisers are heavily focused on engaged users rather than playing the numbers game and aiming for high install volumes. This translates into significantly lower CPI rates that are complimented by a sophisticated in-app and CPA structure.

This structure encourages publishers to provide quality users that engage with their apps and directly translated into a very low install fraud rate of only 3.8%.

However, this doesn’t mean that gaming apps are immune to fraud, as fraudsters have begun shifting their focus towards these CPA in-app events, with rowing in-app fraud presence measured year-over-year.

On the other end of the install fraud scale we can find several non-gaming verticals, specifically Finance apps.

High install fraud presence in finance apps can be associated to several factors such as:

- Large scale marketing budgets

- Lower awareness to digital KPIs – established banks or investment firms taking their “first steps” in digital advertising

- Highest average CPI rates in the market

Travel and shopping apps are not far behind, and also suffer significant install fraud rates due to their relatively high CPIs and marketing budgets. However, these verticals are generally more familiar with online KPIs, having historically operated online since the early desktop days.

The average install fraud rate for non-gaming apps currently stands at 31.8%, meaning almost one in three app installs is fraudulent

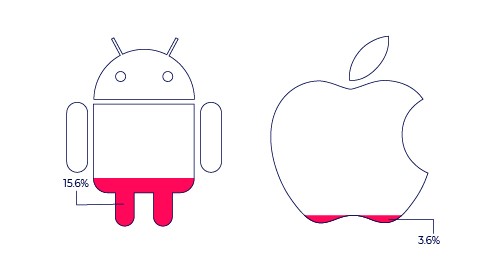

iOS vs. Android

When examining app install fraud by operating system, Apple’s iOS is significantly vulnerable, while Android users suffer from over 6x higher install fraud rates.

Apple’s iOS takes the walled garden approach, which includes a strict vetting process for apps seeking to enter its store, and thus creating a safer environment for its users. However, iOS devices still suffer from click flooding fraud attempts, as this fraud tactic bypasses store regulated defenses.

Android, on the other hand, operates an open-for-all OS, which attracts fraudsters seeking opportunities and loopholes to exploit.

Unlike Apple devices, Android devices also allow users to download off-store apps.

These apps can be found outside the traditional app stores (GooglePlay and AppStore) and offer the stripped APK version of the app shown to the user.

These stores are open to everyone, without ANY filtering process, and malicious apps often infect them. This accumulates to Android’s high install fraud rate, as off-store apps often service fraud operations by injecting devices with malware and adware, without the user’s knowledge or consent.

Post attribution detection

Fraud detection attempts must carry on beyond the point of install attribution, as fraud attempts have been increasingly targeting in-app events over the past few years.

Fraud methods constantly evolve and adapt to anti-fraud solutions – improving their ability to carry out install fraud schemes by avoiding install fraud detection logic. Additionally, fraudsters increasingly turn their attention towards more lucrative CPA targets rather than focusing solely on CPI rates, applying new methods that are specifically designed to bypass standard install fraud detection methods.

These new methods can only be identified retrospectively – after the install was attributed.

By doing so, newly introduced fraud methods can be flushed out by assigning them to new fraudulent clusters and patterns that may have not been familiar at the point of their initial attribution.

Installs that helped establish this new reasoning can then be denied after they were attributed to fraudulent sources. This can only happen retrospectively once their cluster reached sufficient statistical significance to accurately be labeled as fraud.

A long standing industry misconception claimed that all fraud attempts can and should be identified and/or blocked in real time. However, AppsFlyer’s unique post-attribution fraud detection solution discovered that at least 18% of fraud attempts on average can only be identified after the point of attribution – exposing yet another market blind-spot.

These are fraudulent installs that would have gone unnoticed had there not been an additional retrospective protection layer.

Financial exposure

Accurately measuring the financial impact of mobile ad fraud is somewhat difficult, as the specific business implications per advertiser vary.

It is, however, possible to calculate the financial exposure to fraud during a given time period (the amount of marketing activity exposed to fraudulent attempts). AppsFlyer measures the definitive majority of mobile marketing activity worldwide ensuring its data is safe to rely on for an accurate estimation.

It is estimated that in 2019 about $4.8 billion were exposed to mobile ad fraud.

The current estimation for the first half of 2020 stands at: $1.6 billion.

Global crisis

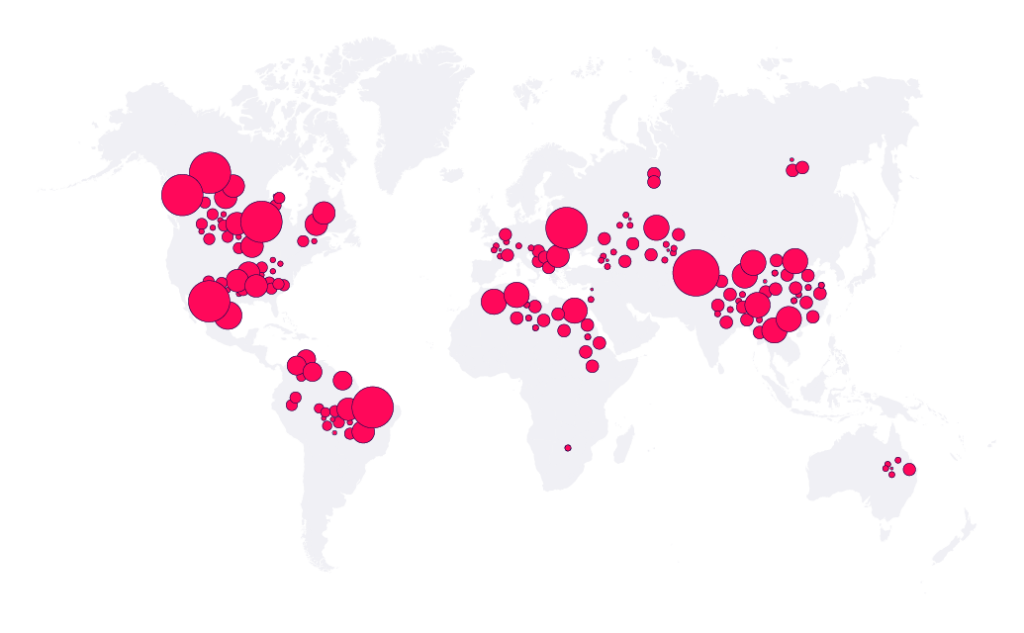

While some may associate fraud to be a region specific issue, this couldn’t be further from the truth.

Keep in mind this guide’s opening statement – wherever the money is, fraud is likely to be there.

And there’s plenty of money to be made through mobile ad fraud worldwide.

Developing markets, who are less technologically advanced, are often less regulated than other more developed markets and are thus ideal for fraudsters to operate. However, through emulators, VPN proxies, and other technological tools borders become irrelevant, allowing fraud to easily infiltrate any country.

Some, more developed, markets like the United States, Canada, and Germany may present lower install fraud rates than others, however these markets often hold the majority of worldwide marketing budgets.

This means that the financial impact on these developed markets with lower fraud rates could potentially be bigger than developing markets with higher fraud rates and less marketing focus.

Higher mobile device accessibility, developed economies, and global consumption culture are all key factors in making mobile ad fraud specifically and online ad fraud in general a global crisis.

Key takeaways

- Mobile ad fraud is an existing and ever growing industry issue, wasting billions of dollars annually.

- Fraudsters are inventive and creative. Their methods evolve over time to adapt and bypass industry regulations and anti-fraud defence mechanisms.

- While mobile ad fraud is regarded under two main categories, methods under these categories can differ in methodology, technology and scale.

- Fraud is a business. Fraudsters are ROI driven, and follow the money wherever it may be.

- Mobile ad fraud is not limited to specific points in the user journey. Nor is it limited to specific verticals or countries. Wherever the opportunity is, fraud will be there.

- An advanced and sophisticated mobile ad fraud solution is a necessity in today’s ecosystem.

A solid and secure infrastructure, combined with an adaptive solution for identification and blocking of existing and new fraud methods is required for any online marketing initiative at any scale.